The TAM Rubberstamp Archive: History, Fluxus, Mail-Art and Rubberstamps

By Ruud Janssen

Figure 1- Marie de la Condamine.

Figure 1- Marie de la Condamine.The fascination about rubberstamps is something that many of us have encountered; whether it be a simple stamp pad, a mounted piece of rubber on a holder, or the ability to just reproduce that simple sign or text on any paper you choose. The creative users of printing techniques agree, this is a very effective and useful printing technique that is accessible for everyone. When older printing techniques became obsolete because of the rise of computers, these rubberstamps survived because they were easy to manage and did not need special equipment, power supply, special techniques, etc.

Historic details about how rubber was discovered is published in the Rubberstamp Album (see reference list Literature). Since this is a rare booklet for the new generation, it is important to know the facts on how it all started.

Charles Marie de la Condamine, French scientist and explorer of the scenic Amazon River, had no idea there would ever be such a thing as a rubber stamp when he sent a sample of “India” rubber to the Institute de France in Paris in 1736.

Prior to de la Condamine, Spanish explorers had noted that certain South American Indian tribes had a light-hearted time playing ball with a substance that was sticky and bounced, but it failed to rouse their scientific curiosity.

Some tribes had found rubber handy as an adhesive when attaching feathers to their person; and the so-called “head-hunting” Antipas, who were fond of tattooing, used the soot from rubber that had been set on fire. They punctured skin with thorns and rubbed in the soot to achieve the desired cosmetic effect. The June 1918 issue of Stamp Trade News indicates that “rubber stamps were made hundreds of years ago…by South American Indians for printing on the body the patterns which they wished to tattoo,” but we have been unable to verify this was actually the case. In New Zealand today, a version of such tattooing is making a hit in the form of rubber stamp “skin markers” which bear intricate figures of birds, snakes, flowers, tribal symbols, etc.

It wasn’t until some thirty-four years after de la Condamine sent his rubber care package home that Sir Joseph Priestley, the discoverer of oxygen, noted: “I have seen a substance excellently adapted to the purpose of wiping from paper the mark of black lead pencil.” In 1770 it was a novel idea to rub out (hence the name rubber) pencil marks with the small cubes of rubber, called “peaux de negres” by the French. Alas, the cubes were both expensive and scarce, so most folks continued to rub out their errors with bread crumbs. Rubber limped along since attempts to put the substance to practical use were thwarted by its natural tendency to become a rotten, evil-smelling mess the instant the temperature changed.

Enter Charles Goodyear. Upon hearing of the unsolvable rubber dilemma (from the Roxbury Rubber Company), Goodyear became obsessed with solving the whole sticky question once and for all. During his lifetime, Goodyear was judged to be a crackpot of epic proportions. Leaving his hardware business, he began working on the problem in his wife’s kitchen, spending hours mixing up bizarre brews of rubber and castor oil, rubber and paper, rubber and salt, rubber and heaven knows what. Daily life intruded on his experiments in the form of recurring bankruptcy and sporadic imprisonment for failure to pay his debts. At one point, Goodyear actually sold his children’s’ school books for the cash required to embark on the next experiment. Goodyear’s persistence and single-mindedness were legion.

In 1839 while fooling around in a kitchen, Goodyear accidentally dropped some rubber mixed with sulphur on top of a hot stove. Instead of turning into a gooey mess, the rubber “cured.” It was still flexible the next day. The process, involving a mixture of gum elastic, sulphur, and heat was dubbed vulcanization, after Vulcan, the Roman god of fire. Vulcanized, rubber lost its susceptibility to changes in temperature. The discovery paved the way for hundreds of practical applications of rubber. In June 1844, Goodyear patented for his process. Never one to rest on his laurels, Goodyear turned his formidable energies to developing a multiplicity of uses for rubber. These continuing experiments were costly and, bless his soul, in 1860 Goodyear died two hundred thousand dollars in debt. His last words reflected the pattern of his life: “I die happy, others can get rich.”

Rubber stamps are considered. a marking device. Today Thomas H Brinkman, Secretary of the Marking Device Association, defines marking devices as, “The tools with which people,…add marks of identification or instruction to their work or product.” The earliest roots in the marking device industry lie with early stencil makers. Many of the first rubber stamps were made by itinerant stencil makers. Since both were marking devices it was a compatible combination. The years from 1866 onward were peppered with the establishment of new stamp companies. Some were stencil makers adding stamps to their repertoire while others focused entirely on making rubber stamps.

Figure 2 – Avulcanizer

Figure 2 – Avulcanizer J.F.W. Dorman is said to have been the first to actually commercialize the making of rubber stamps. He started as a sixteen-year-old traveling stencil salesman in St. Louis and opened his first business in Baltimore in 1865. In 1866 he learned the technique of making rubber stamps from an itinerant actor who claimed he learned the skills from the inventor. Dorman made his first stamps under cover of night with his wife’s assistance in an effort to keep the process a secret. Dorman was an inventor, and his contributions to the industry were numerous. His eventual specialty was the manufacture of the basic tools of the trade – the vulcanizer. His company continues in business today.

The first stamp-making outfit ever exported from the U.S. to a foreign country was shipped by R.H.Smith Manufacturing Company to Peru in 1873. Back on the home front, companies continued to spring up. In 1880 there were fewer than four hundred stamp men, but by 1892 their ranks had expanded to include at least four thousand dealers and manufacturers. An amazing number of these first companies are still in business today, frequently under their original names or merged with others whose roots lie in the mid and late 1880’s.

It was a small, tight knit industry, characteristics which it retains today. The longevity of the companies is no more astounding than the attitude of the stamp men themselves. Once in the business, people tended to stay loyal to it. During our research, we were amazed at the number of people who had spent forty or fifty or more happy years in the industry.

Early stamp makers tend to be colorful, and many frontier like exploits dot the landscape. Louis K Scotford and his companion Will Day set off across Indian Territory to the settlements in Texas carrying their stamp-making equipment in an old lumber wagon. The country was wild and rugged in 1876, frequented by bandits and Indians. L.K. and Will solicited orders during the day, made the stamps at night, and delivered the following day in time for the intrepid pair to harness up and head out once again. It was a romantic adventure and not unprofitable. At the end of their three-thousand mile trek, the two returned to St. Louis with two twenty-five pound shot bags filled with silver dollars.

Charles Klinkner, who established his West Coast stamp house in 1873, would have been the pride of any modern day publicity agent. Klinkner was prone to calling attention to his wares in startling, unorthodox ways. He rode around San Francisco and Oakland in a little red cart drawn by a donkey rakishly dyed a rainbow of colors. To make his stamps sound like something extra special, he advertised them as “red rubber stamps”, and people were convinced that it meant something. At the time, almost all stamps were made from red colored rubber. Ah, the power of suggestion.

After years of talk and numerous attempts to organize, the industry formed a national trade organization in 1911. M.L. Willard and Charles F Statford, who had worked long and hard toward organizing the stamp men, saw their work bear fruit when the first marking-device trade convention took place at the LaSalle Hotel in Chicago June 20th 1911. It was the beginning of a new era and even pioneer stamp personage. B.B. Hill, the father of the “mechanical hand stamp”, then eighty years old with fifty years in the business behind him, was on hand to hear the International Stamp Trade Manufacturers Association voted into existence. Today the organization is known as the Marking Device Association and is headquartered in Evanston, Illinois.

A number of trade journals served the industry: Stamp Manufacturer’s journal, Stamp Trade News, Marking Devices Journal, and now Marking industry magazine. Since 1907, the publications have reflected serious industry discussions about trade ethics, price controls, planning by scientific management, and marketing, mixed with folksy anecdotes about who was playing which sport for charity and tidbits about a 175-pound swordfish off the Californian coast. Pricing information was colorful on occasion as witnessed by this quote from the February 1909 Stamp Trade News: “No blood flows from a turnip nor does wealth flow from rubber made into rubber stamps at ten cents per line.” The same issue proffered a real gem from a column called “Pen Points” – “Rubber stamps made while you wait is not a good sign to hang out. It makes it look too easy.”

The rubberstamp used as a tool for artists is also described in the Rubberstamp Album. The details are also available online: http://www.customstampsonline.com/Pages/History02.aspx . Knowing the historical background of rubberstamp making is essential to any artist using this medium and for art critics for chronological purposes. Some artists create new ways of stamp making and some are inspired by history, in the network you encounter both.

Figure 3 – Kurt Schwitters

Figure 3 – Kurt SchwittersHistorical facts:

One of the first to integrate the rubber stamp in works of art was German artist/poet Kurt Schwitters, who dubbed his art activities “Mertz” (from a scrap of paper with the word KOMMERTZ used in one of his early collages. “Mertz” applies to the bulk of Schwitters work, and not exclusively to the pieces incorporating rubber stamps. As early as 191 he created “Merz rubber stamp drawings”, which were an amalgam of pasted bits of paper, drawings and stamp impressions made with common, functional stamps that bore phrases such as BELEGEXEMPLAR (Review Copy) and BEZAHLT (Paid). A hefty art tome entitled “Kurt Schwitters” written by Werner Schmalenbach shows four examples of Schwitter’s works containing rubber stamp impressions. Probably the first book of rubber stamp works was Schwiter’s “Sturm Bilderbuch IV” published in Berlin in 1920, which contains fifteen poems and fifteen rubber stamp drawings.

An article in the Special Catalogue Edition of La Mamelle’s “FRONT” written by Ken Freidman and Georg M. Gugelberger, dates the introduction of the stamp into contemporary art to Ben Vautier’s use of a rubber stamp (LART CEST) in his works in 1949.

Both German artist Dieter Roth and French artist Arman began using stamps heavily in their works in the 1950’s. From the late 1950’s onward the number of artists and writers using stamps in their works expanded tremendously and the range of works widened to include not only hand-stamped. limited edition books and prints but sculptures, paintings, and multiples as well. In 1968, Multiples. Inc (New York) published a project called “Stamped Indelibly” containing work by such other well known artists such as Marisol, Oldenburgh, Warhol Indiana and others.

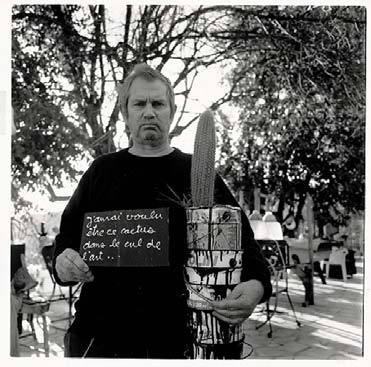

Figure 4 – Ben Vautier 1990

Figure 4 – Ben Vautier 1990Much of the stamp activity in the 1960’s stemmed from the Fluxus movement, a loose-knit international avant group somewhat Dada in spirit, whose participants included Joseph Bueys, Robert Filliou, Ken Freidman, Dick Higgins, Yoko Ono and Ben Vautier. Freidman and Vautier are said to have published in 1966 the first multiple to include rubber stamps as physical objects. Published by Fluxus, it was called “Fluxpost Kit” and contained stamps by both artists. Even a partial listing of artists involved with stamp activities during the last several decades is a long one: Charles Amirkhanian, Anna Banana, George Brecht, Fletcher Coop, Herve Fischer, Bill Gaglione, J H Kochman, Carol Law, Emmet Williams, and on. And then, of course, is Saul Steinberg.

Stienberg’s work frequently appears in The New Yorker Magazine, and has incorporated rubber stamps into his work for years, sometimes stamped in ink, sometimes in oil paint. A major Steinberg exhibition organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art contained numerous pieces dotted with the rubber stamps Steinberg considers personal. Since little has been written on rubber stamps and the artist, two books are especially important to know about. According to the Freidman/Gugelberger article in FRONT, Czech artist J H Kocman’s book “Stamp Activity”, published in a limited, thirty-edition copy in 1972, was “the first true anthology of stamps and their use by artists”. Herve Fischer’s book “Art et Communication Marginale, Tampons d’artistes” was published by Editions (Paris) in 1974., devotes almost two hundred pages to whole stamp works or selections from artist’s collections. In most cases, brief biographical information about the artist is also supplied.

In this text from the Rubber Stamp Album they’ve indicated very little about the Dada movement’s influence on Stamp Art. At the beginning of the last century, the Dada movement made a major impact to the art world, with Kurt Schwitters being one of the only people involved. The use of fonts and lettering in the work of Dada proceded rubberstamps, but it was during the Stamp Art movement that the quick printing method was initiated.

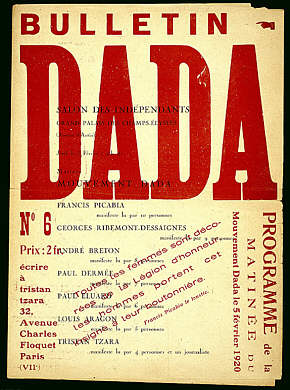

Figuur 5 – Dada 6 (Bulletin Dada), ed. Tristan Tzara (Paris 1920) – cover

Figuur 5 – Dada 6 (Bulletin Dada), ed. Tristan Tzara (Paris 1920) – coverFor an extensive text on the Dada-movement in New York and the impact of Tzara and Picabia, please visit: http://www.artic.edu/reynolds/essays/hofmann2.php. I have included a selection of work that gives you a historical perspective of the use of rubberstamps.

From: Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection.

The same year Tzara introduced his review Dada in Zurich, related activities took place in New York. Not unlike Zurich, New York had become a refuge for European artists seeking to escape the war. For artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, the American city presented great potential and artistic opportunity. Soon after arriving there in 1915, Duchamp and Picabia met the American artist Man Ray. By 1916, the three men had become the center of radical anti-art activities in New York. While they never officially labeled themselves Dada, never wrote manifestos, and never organized riotous events like their counterparts in Europe, they issued similar challenges to art and culture. As Richter recalled, the origins of Dadaist activities in New York “were different, but its participants were playing essentially the same anti-art tune as we were. The notes may have sounded strange, at first, but the music was the same.”[14]

The anti-art undercurrents brewing in New York provided an ideal climate for Picabia’s provocative journal 391. Published over a period of seven years, 391 is the longest running journal in the Mary Reynolds Collection. The magazine first appeared in Barcelona in 1917, and was modeled after the pioneering journal 291, which was published under the auspices of the photographer and dealer Alfred Stieglitz.[15] Picabia was able to put out four issues of 391 in Barcelona with the support of some like-minded expatriates and pacifists.

Although 391’s corrosive spirit was only just emerging in these early issues, the anarchic attitude that would later define the magazine and its editor is already apparent. These first issues introduce, for example, a section devoted to a series of bogus news reports. As Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia recalled, this feature began as a mere joke and “quickly degenerated in subsequent issues into a highly aggressive system of assault, defining the militant attitude which became characteristic of 391.”[16] These early issues include literary works by poet Max Jacob, painter Marie Laurencin, and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, as well as by Picabia, and feature cover illustrations of absurd machines designed by Picabia.

By the time Picabia took 391 to New York at the end of 1917, the magazine had assumed a decidedly assertive and irreverent tone. The New York editions of 391, issues five through seven, celebrate Picabia’s nihilistic side and his love of provocation and nonsense. Buffet-Picabia had this to say about 391:

It remains a striking testimonial to the revolt of the spirit in defense of its rights, against and in spite of all the world’s commonplaces…Without other aim than to have no aim, it imposed itself by the force of its word, of its poetic and plastic inventions, and without premeditated intention it let loose, from one shore of the Atlantic to the other, a wave of negation and revolt which for several years would throw disorder into the minds, acts, works, of men.[17]

Picabia’s three New York issues feature contributions by collector Walter Arensberg, painters Albert Gleizes and Max Jacob, and composer Edgar Varése.

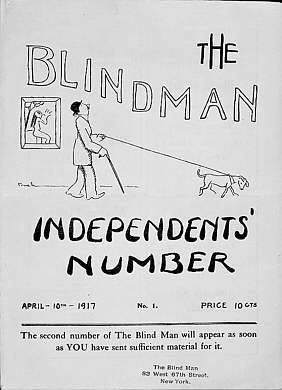

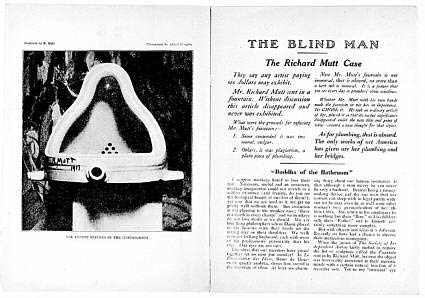

While Picabia was involved primarily with the group of artists surrounding Alfred Stieglitz and with the publication of 391, Duchamp made connections with Arensberg, through whom he became involved in the Society of Independent Artists. It was this organization, interested in sponsoring jury-free exhibitions, that gave Duchamp the idea for The Blind Man—a publication that would invite any writer to print whatever he or she wanted. The inaugural issue, published on April 10, 1917 by Duchamp and writer Henri-Pierre Roché, has submissions by poet Mina Loy, Roché, and artist Beatrice Wood. Emphasizing the informal editorial policies and uncertain future of The Blind Man, the front cover proclaims, “The second number of The Blind Man will appear as soon as YOU have sent sufficient material for it.” When this hastily published first issue came out, the editors realized that they had forgotten to print the address of the magazine on the cover. To remedy this, a rubber stamp was created and used to imprint this information on the front cover of each issue.[18]

Figure 6 – The Blind Man 1. eds. Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, Henri-Pierre Roché – 1917 New York

Figure 6 – The Blind Man 1. eds. Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, Henri-Pierre Roché – 1917 New York

Since Duchamp and Roché were not American citizens, and therefore faced possible conflicts with authorities, Beatrice Wood stepped forward to assume responsibility for The Blind Man. Because her father subsequently protested her involvement (due to the periodical’s content), it was decided that rather than making it available to mainstream audiences through newsstands, The Blind Man would be distributed by hand at galleries.[19]

The second issue of The Blind Man came out two months after the first,[20] following the opening of the Society of Independent Artists’ 1917 exhibition and the rejection of Duchamp’s infamous entry Fountain, a urinal that the artist signed with a fictitious name and anonymously submitted as sculpture. This issue features Stieglitz’s photograph of Fountain and the editorial “The Richard Mutt Case,” which discusses the rejection of Duchamp’s entry. Also included in this issue were contributions by Arensberg, Buffet, Loy, and Picabia, among others.

While The Blind Man had caught the attention of the New York art community, a wager brought an early end to the magazine. In a very Dada gesture, Picabia and Roché had set up a chess game to decide who would be able to continue publishing his respective magazine. Picabia, playing to defend 391, was triumphant: Roché and Duchamp were forced to discontinue The Blind Man.[21]

Figure 7 – The Blind man 2, eds Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, Henri-Pierre Roché – 1997 New York

Figure 7 – The Blind man 2, eds Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, Henri-Pierre Roché – 1997 New York Following the early demise of The Blind Man, Duchamp launched another short-lived magazine. Edited by Duchamp, Roché, and Wood, Rongwrong (May 1917) carries contributions by Duchamp and others within Arensberg’s circle, as well as documentation of the moves from Picabia’s and Roché’s infamous chess game. Duchamp intended the title of the magazine to be Wrongwrong, but a printing error transformed it into Rongwrong. Since this mistake appealed to Duchamp’s interest in chance happenings, he accepted the title.

The appearance of the journal New York Dada (April 1921) ironically marked the beginning of the end of Dada in New York. Created by Duchamp and Man Ray, this magazine would be the only New York journal that would claim itself to be Dada. Wishing to incorporate “dada” in the title of this new magazine, Man Ray and Duchamp sought authorization from Tzara for use of the word. In response to their tongue-in-cheek request Tzara replied, “You ask for authorization to name your periodical Dada. But Dada belongs to everybody.”[22] In addition to printing Tzara’s response in its entirety, this first and only issue also carried a cover designed by Duchamp, photography by Man Ray, poetry by artist Marsden Hartley, as well as several illustrations. As with so many self-published artistic journals, this first issue was neither distributed nor sold, but circulated among friends with the hope that it would generate a following. New York Dada, however, was unable to ignite any further interest in Dada. By the end of 1921, Dada came to an end in New York and its original nucleus departed for Paris, where Dada was enjoying its final incarnation.

Figure 8 – One of the hand carved stamps in the archive by Eberhard Seifried, Germany.

Figure 8 – One of the hand carved stamps in the archive by Eberhard Seifried, Germany.Originally the rubberstamp was made for a special user-group of people. They were the decision makers that had access to their stamps and by using it, authorized certain decisions. The art-forms that avoided the settled art world embraced the possibilities to use their own rubberstamps and to ridicule certain hierarchies in these closed circles.

The Rubberstamp was originally focused on text, but in the Mail-Art and Fluxus worlds, the texts artists wanted to create and print ,were not of the typical manner. This lead to new creative styles of stampmaking. During the sixties and seventies, reproduction was difficult. The copy machine was not easily accessible, so to quickly reproduce a text or a document people used the rubberstamp method.

Figure 9 – Sample of one of the address lists of the archive

Figure 9 – Sample of one of the address lists of the archiveAs a young boy, I grew up watching my father use a personalized name stamp and by the age of 14 , I had saved enough money for my own. In 1980, I was 21 then, I discovered the Mail Art Network. The Mail Art Network opened a whole new way of learning, exploring, and communicating with the use of stamps to other “worlds”.

In 1983, I decided to collect the prints of Mail-Artists I was in contact with. That was the start of sending and receiving numbered stamp sheets. Every sheet was given a printing date and a unique number to keep track of them. The lay-out and text of the sheet was only slightly updated over the years. Seeing a selection of the archive that spans almost over 30 years will explain the development best. Besides the many Mail-Art projects I have done, this one has been going on for decades. Almost every mail-artist I was in contact with received such a sheet. I also sent out collage stamp sheets to broaden the scope of the collection. It was the same structure but more than one mail-artist would work on the paper. This meant the receiver of a blank sheet could choose an artist unfamiliar to me which in turn, expanded my network quite rapidly. Furthermore, making additions to other artist’s work created a whole new dimension of collaboration.

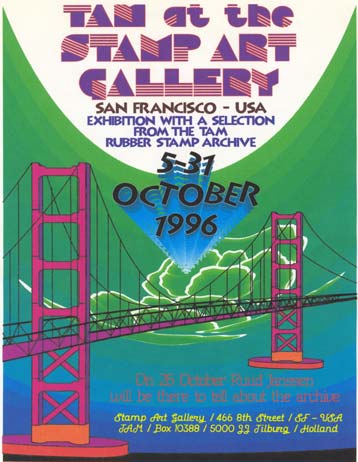

Figure 10 – Poster of the exhibit of the TAM-Rubberstamp Archivein San Francisco (1996)

Figure 10 – Poster of the exhibit of the TAM-Rubberstamp Archivein San Francisco (1996)Documenting the complete collection started to become a problem. In the beginning I had hand typed lists. Every month the new contributions came in and I added them to the list on a typewriter. They were reproduced several times and distributed continually into the network. Some of them also ended up with John Held Jr. in USA, and he even eventually sent them to the MoMa Mail-Art collection. With my strong computer skills, I made a database in the eigthies in which I kept the details of the collection and the participating artists. The lists produced during that time, were sorted by country and with the use of the program “Reflex”, at that time was an advanced relational database, I was able create a more detailed report. That documentation was printed and bound into booklets that I sent into the network periodically. The long, historic address list came in handy for many other mail-artists that wanted to explore their network. It grew into a booklet of over 40 pages with thousands of addresses and countries that vanished (USSR, East-Germany, Yugoslavia, etc..) and countires newly created (Croatia, Russia, Latvia, etc..). At a certain point, the number reached over two thousand; it was growing too rapidly, so the database was not continued. The number of sheets in the collection grew to over ten thousand and to maintain a complete list would demand too much work.

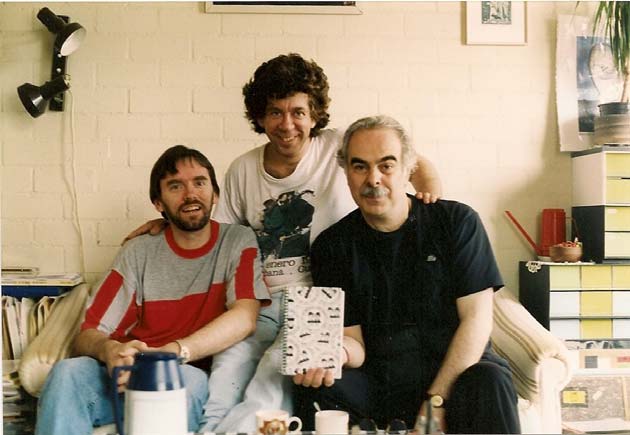

Figure 11 – Me, John Held Jr. and Bill (Picasso) Gaglione – Showing the original booklet with the stamp prints Tilburg Netherlands 1995.

Figure 11 – Me, John Held Jr. and Bill (Picasso) Gaglione – Showing the original booklet with the stamp prints Tilburg Netherlands 1995.After documenting the collection, exhibiting was the next phase. During the time, that I was looking for a place to exhibit, John Held Jr. had started to work with Bill (Picasso) Gaglione in San Francisco. They were doing these wonderful exhibitions in the Stamp Art Gallery and in 1996 they asked me if I wanted to be a part of the TAM Rubberstamp Archive exhibition. Instead of sending them the sheets, I did a special project where all new sheets would go straight to San Francisco, and I wouldn’t be present for the opening. I decided instead to give a lecture about TAM and the Stamp Archive. I also conducted, without people knowing in advance, lots of mail-interviews with people I met during that journey. For more details, please see the link list in the appendix of this essay. The catalogue of this first exhibition was produced by the Stamp Art Gallery and contained reproduction of all the sheets. During that time, I was in San Francisco and surrounding areas for two weeks and met a lot of people that I am happy to be acquainted with. (See report on: http://www.iuoma.org/reis_usa.html) .

When John & Bill were in Europe for one of their Fake Picabia Tours they decided to also visit Tilburg, where I was living at the time. Bill tried to stamp as much of the originals as possible during the short stay in my apartment. He printed quite a lot and eventually that collection was documented in another publication they created.

Figure 12 – Rubberstamp madein an edition of 150 and distributed into the network.

Figure 12 – Rubberstamp madein an edition of 150 and distributed into the network.The collection of the TAM Rubberstamp Archive focuses mainly on these stamp sheets. Rubber itself loses its printing function as soon as the rubberstamp isn’t used anymore. The special oil the rubberstamp ink consists of prevents the rubber from getting hard. Once it gets hard, the quality of the stamp goes rapidly backwards and archiving the rubber is just archiving the artifact; the message, text or image can’t be reproduced anymore. That is the basic reason for starting the archive, to preserve on paper the prints of all those users and to keep the images alive for now almost 3 decades.

In the nineties, I was in close contact with some of the rubberstamp firms that emerged in both Europe and the USA. During that time, I was contacted twice by the magazine ‘Rubberstampmadness’ to do an interview that was to be published. At Stempel-Mekka (Germany) I even gave workshops on eraser carving and to my surprise found Anna Banana was there as well. Wolfgang Hein allowed me to use his walking rubberstamp in the logo and it was produced in an edition of 150. Those editions were used to create a name for the archive and were sent out as gifts to the people who continually sent in stamp sheets.

Figure 13 – One of the Stampsused in Performances for Fluxus Heidelberg Center

Figure 13 – One of the Stampsused in Performances for Fluxus Heidelberg CenterSince 1996, I traveled intensively to Heidelberg in Germany for about 7 times a year. It was in that beautiful city, I was able to meet with Litsa Spathi. Spathi is a talented painter and a conceptual artists who focuses on Object books and produces a lot of Fluxus Poetry. In 2003, she had the idea to combine the three words Fluxus, Heidelberg, and Center into one Institute and it became the start of the Fluxus Heidelberg Center (see www.fluxusheidelberg.org). Rubberstamps were included in a lot of performances, as well as the new advanced tools. They all became a part of the future of Fluxus. We knew then that life is a constant Flux. The Fluxus Heidelberg Center is currently located in Breda (Netherlands) and in Athens (Greece).

All stamp performances from the beginning are documented in the book that was published to record the first years of the center. (For all details see: http://www.lulu.com/content/4108181). There was a lot of documentation in the 251 pages, including photos. For the printing of the book, we used the newest possibilities, i.e. on-demand publishing and distribution of the book. There is even a complete color version which is available for libraries and collectors at: http://www.lulu.com/content/3996203.

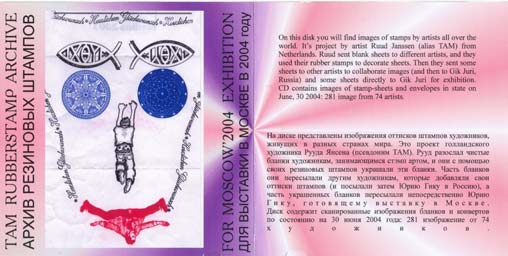

Figure 14 – Printed catalog Moscow Exhibition

Figure 14 – Printed catalog Moscow ExhibitionIn 2004, a second exhibition of the rubberstamp archive was completed, but this time in Moscow and by invitation of Gik Juri. The location was the famous L-Gallery in centre of Moscow. The concept this time was the same, but the sheets would go directly to Moscow. Unfortunately, because of too many travel plans and differences in opinion I never made it to Moscow. Even to this day, those sheets were never returned to the archive and are still in the collection of Gik Juri. When I requested the return of the sheets for the archive years later, he claimed to have lost them. The catalog this time was made in digital form; a CD with videos, digital scans of every sheet, and video images of how the show was presented on the Russian television. A hard copy of the text and catalogue is available at: http://www.lulu.com/content/1862885

Figure 15 – Cover of the CD produced for the exhibitionin Moscow at the L-Gallery.

Figure 15 – Cover of the CD produced for the exhibitionin Moscow at the L-Gallery.In 2005, major changes happened in my life. I moved out of Tilburg, got married, and started a new job in Breda. The complete archive traveled with me in boxes and had much more space. It is still a private collection, but because of my work with the internet and the digital environments, I was able to place a lot of information online. By doing it online, a lot of my archive, texts, and art became available in digital format. I even had the printed catalogue, that contains part of the documents of the exhibition, available on the Internet and can be ordered as a book.

After debates whether to continue the growth of the archive, it was decided that we would continue sending out the stamp sheets but this time with the Breda Address. Over the years I kept lists of how many sheets were sent out. Each sheet had a number to keep record of the count but a lot of them were never returned. I had an idea of why sheets were not returned. I realized since every sheet was hand stamped, some people started to collect the sheets. Every sheet was dated, which meant they were not just simple copies but were individually hand stamped by me. I guess the collage stamp sheets ended up in some collections of other mail-artists. I even saw some of the sheets on documentations of mail-art shows.

Figure 16 – Special group on the IUOMA network discussing and exchanging Rubber Stamp Art – 2010

Figure 16 – Special group on the IUOMA network discussing and exchanging Rubber Stamp Art – 2010During the last years, there were visible changes. It was predicted that the mail art network would decrease in volume because of the new electronic communication tools and in the beginning of the new millennium it happened. Although learning how to use the computer for communication and having the ability to digitize and publish your images and videos online hindered the usual ways of mail-art, the networks found each other again and the old generation of networkers discovered the new generation of networkers. On the social network I created for IUOMA in November 2008 (International Union of Mail-Artists , see: http://iuoma-network.ning.com/) the number of mail-artists online had increased to almost 1,000. Artists that discovered the concept of Mail-Art online, started to send out traditional mail. New and old Fluxus artists discovered the Internet and used it a lot. Even in the Mail-Interviews with Dick Higgins, Ken Friedman and Alison Knowles questions and answers went back and forth in a digital way.

In 2010, a new exhibition will show a part of the TAM Rubberstamp archive; this time in New York at the Mary Stendhal Gallery which will include parts of the “Greetings from Daddaland: Fluxus, Mail Art and Rubber stamps” curated by John Held Jr. and Picasso (Bill) Gaglione. The many projects I did, crossed a lot of paths with Fluxus artists and Fluxus-related artists. Many people that associate themselves with mail-art have sent in stamp sheets with their specific use of rubberstamp on that small piece of paper. There was no time to have a restart of the concept to send in sheets directly to the Gallery. So this time a special selection of sheets documenting how Rubber has been used in the last three decades will be exhibited and, of course, a focus on some of the names that are associated with that large circle of friends that gathered around the curators of the show: John Held, Jr. and Picasso (Bill) Gaglione. The exhibited part of the collection will include artists such as: BuZ blurr, M.B. Corbett, Litsa Spathi, John M. Bennett, Dick Higgins, Robert Rehfeldt, Rea Nikonova, Joseph W. Huber, Robert Rocola, Jan Cremer, Robin Crozier, Bern Porter, Dieter Albrecht, John Held Jr., Picasso Gaglione, H.R. Fricker, David Cole, John Evans, Carlo Pittore, and a large list of Mail-Artists that are well-known to the network. All sheets that were originally sent in for the Stamp Art Gallery exhibition will now be in New York.

The Rubberstamp has had such an important place in both Mail-Art and Fluxus. If you follow the life around you and reflect it in your art, there is always the factors of time and fun. A rubberstamp is easy to make, fast to make, and always available. It can be used for so many different purposes and it is such a handy multifunctional tool that was originally intended just for bureaucrats. The fun of rubberstamps is that the owner can be exchanged. A lot of rubberstamps are designed and made by the artists but are also exchanged or sent as a gift. All these images go around the globe and the temporary owner of the set can print them as long as they have access. There are even special projects done where a rubberstamp travels the globe and the temporary user can use the rubberstamp for a month. Some original rubberstamps of the Archive have found new homes as well. Some eraser carved stamps were made on location, so they reflect the situation one is in. Both are typical tools for a Fluxus- or a Mail-Artist. Who is to say whether an artist fits in just one category. Life keeps changing, and I know I am always going with the new things that I encounter.

Most samples of how Rubberstamps can be used, in both Mail-Art and Fluxus are documented in several books. I have added a small list of informative reference books. The TAM Rubberstamp archive is a growing collection and every week new sheets come in and empty sheets are sent out. As long as rubberstamps are used by artists, they will eventually get a sheet one way or another. Analyzing the collection is something that still needs to be done. Showing parts of the collection to a broader public is the start.

Ruud Janssen , March 21, 2010.

Literature:

1. John Held Jr. – “L’arte del Timbro” edited by Baroni, Vittore, Italy. ISBN: 88-86828-23-3 – AAA Edizioni. [1999]

2. Herve Fischert – “Art et Communication Marginale, Tampons d’artistes” was published by Editions (Paris) in [1974].

3. Rubberstamp Album by Joni K. Miller & Lowry Thompson – The complete guide to making everything prettier, weirder, and funnier. How and where to buy over 5,000 rubber stamps. And how to use them. ISBN 0-89-480-045-0 Rainbird Publishing Group – Workman Publishing, New York. [1978]

4. L’art du Tampon – Expo Paris. Edited by the “Musée de la Poste” in Paris – France. [1995]

5. Rubber Stamper’s Bible, Author: Francoise Read, USA , ISBN-13: 978-0715318515 , Publisher: F & W Publications [2005].

6. Rubber Soul, Author: Sandra Mizumdo Posey, Publisher: Jackson University Press Mississippi [1996]

7. Rubber Stamps – Klaus Groh, Edewecht, Germany, Edition des Dada Research Centre, [1983?]

Contact Details:

Ruud Janssen

TAM-Publications

P.O. Box 1055 4801 BB Breda NETHERLANDS

Harry Stendhal

Stendhal Gallery

545 West 20th Street

New York, NY 10011

2123661549

Online Details:

TAM-Rubberstamp Archive : http://tamrubberstamparchive.blogspot.com/

IUOMA-Network : http://iuoma-network.ning.com/

Mail-Interviews : http://mailinterviews.blogspot.com/

IUOMA Bookshop : http://stores.lulu.com/iuoma

About the Author

Ruud Janssen was born at Tilburg, Netherlands. He studied Technical Physics at the University in Eindhoven and Physics/Mathematics at the Teachers College in Tilburg. He became active with mail art in 1980s and organized many international mail art projects. In 1988 he founded the IUOMA (International Union of Mail-Artists). Since 1983 he has been the curator of the TAM-Rubberstamp Archive. In 1994, he started his legendary Mail-Interviews which have been published as booklets and online, they are now also available at the MoMa in New York. He has conducted interviews with Fluxus and mail artists in many different communication forms. The interviews now have a new concept where the question is sent in a specific communication form and the person interviewed chooses his own way to get the answer back. By doing it this way, the factor time is involved in each specific interview. In 2003 Ruud Janssen co-founded the Fluxus Heidelberg Center which was initiated by Litsa Spathi. Since 2005, Ruud Janssen has resided in Breda, Netherlands. Janssen publishes articles, magazines, and booklets with his TAM-Publications.

2 thoughts on “Essay by Ruud Janssen”

Picasso, so L and I could not be there (indy-anna) but what we’ve seen, this looks like a great show.

Wondering if there’s a catalog????

Cheers! CM & L

Picasso,

Sorry I missed your show when you were in town. The gallery in the picture looks beautiful. You are becoming famous and I suppose congratulations are in order. Mozaltov!!

Moose