Yvelyne Wood’s Auschwitz

by Professor Donald Kuspit

State University of New York at Stony Brook

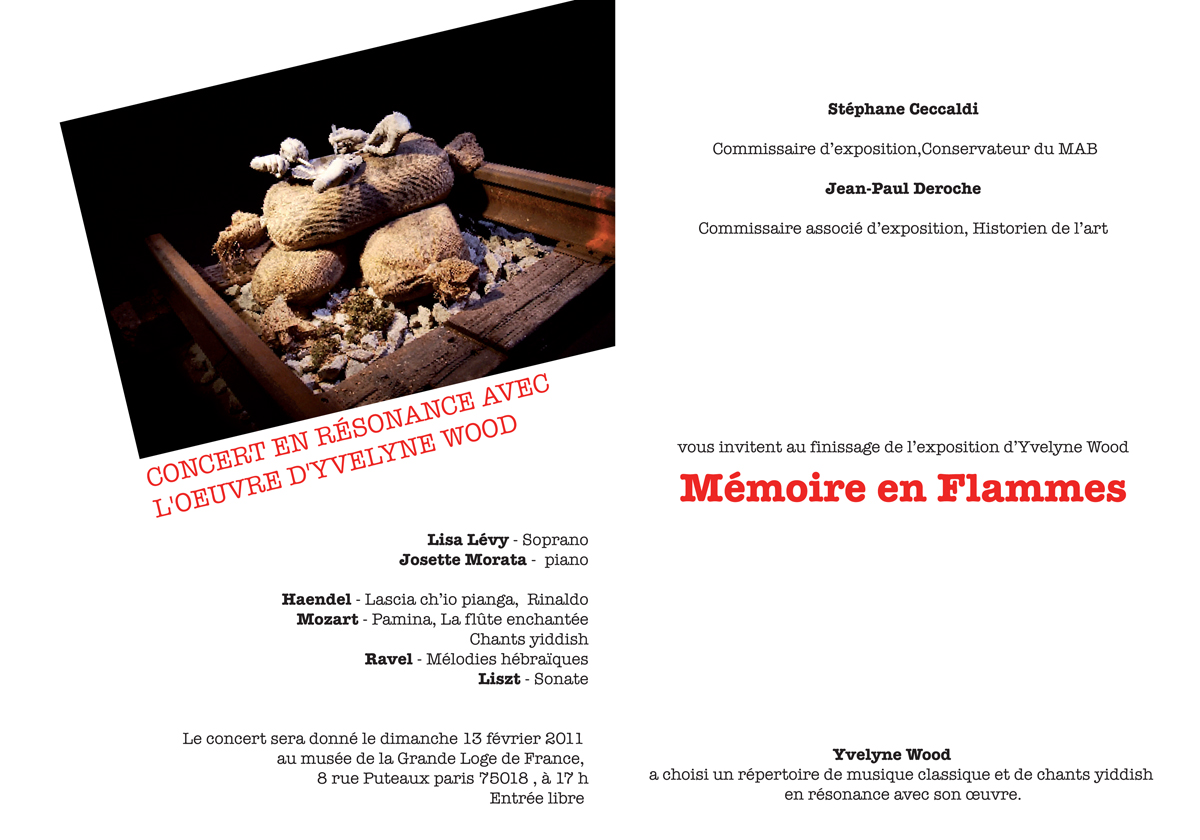

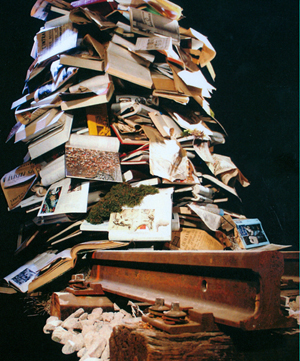

Memoire en Flamme (2010)

220 x 329 x 185 cm,

Installation 700 livres environ,

journaux datant de la 2eme Guerre Mondiale,

rails de chemin de fer,

balastes, traverses.

Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes(1)

War is war, l’art pour l’art, in politics there’s no room for compunction, business is business, –all these signify the same thing, all these appertain to the same aggressive and radical spirit, informed by that uncanny, I might almost say metaphysical, lack of consideration for consequences, that ruthless logic directed on the object and on the object alone, which looks neither to the right nor to the left; and this, all this, is the style of thinking that characterizes our age.

…In the violence of this revolution caused by the radical application, one might even say by the unleashing, of logic, in this removal of the point of plausibility to a new plane of the infinite, in this withdrawal of faith from concrete life, the simple sufficiency of existence was destroyed.

Hermann Broch, The Sleepwalkers(2)

Auschwitz confirmed the philosopheme of pure identity as death…. Absolute negativity is in plain sight and has ceased to surprise anyone…. What the sadists in the camps foretold their victims, “Tomorrow you’ll be wiggling Skyward as smoke from the chimney,” bespeaks the indifference of each individual life that is the direction of history. Even in his formal freedom, the individual is as fungible and replaceable as he will be under the liquidators’ boots.

… Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream; hence it may have been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems. But it is not wrong to raise the less cultural question whether after Auschwitz you can go on living….

Theodor W. Adorno, Negative Dialectics(3)

Europe died in Auschwitz.

Sebastian Vilar Rodriquez, “All European Lift Died in Auschwitz”(4)

It is important, for the fullest understanding of Yvelyne Wood’s sculptural installations-her four masterworks addressing the holocaust-to realize that she is French: her art presents itself, in no small part (if unconsciously), as an act of atonement for French anti-Semitism, if also, consciously, as a protest against it. The inclusion, in Burning Memory or The Last Journey, 2010 of original documents from the time of the French Collaboration with the Nazis-and, astonishingly, of an original article written by the Jewish officer Albert Dreyfus while in prison on a trumped up charge of betraying France–suggests how wide-spread French Anti-Semitism was in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Even earlier, if Voltaire’s contempt for the Jews is symptomatic of the French attitude to them: “You will merely find in Jews an ignorant, lazy, barbarous people who for a long time have combined the most undignified stinginess with the most profound hatred for all the people who tolerate them and enrich them.”(5) Voltaire may have been an Enlightenment thinker, but he was not enlightened about the Jews. He was in fact more barbarous than he thought they were, if we agree with the historian Eric Hobsbawm’s definition of barbarism as the “reversal of the project of the eighteenth-¬century Enlightenment, namely the establishment of a universal system of…rules and standards of moral behaviour, embodied in the institutions of states dedicated to the rational progress of humanity: to Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness, to Equality, Liberty and Fraternity.”(6) French Anti-Semitism contradicted and betrayed the humanistic ideals of the French Revolution by depriving Jews of the Equality, Liberty, and Fraternity for which it was fought, in effect dehumanizing them.

Wood’s art damns France for this moral failing-for its vicious hypocrisy. There is a personal animus to her art, a defiant air of angry futility: like Zola’s famous attack on the French government for its treatment of Dreyfus, Wood’s art is her defiant “J’accuse.” Like Zola, Wood cannot undo the injustice that has been done, but she can memorialize it by shaming France into self-consciousness, and asserting her fraternity with its Jewish victims, in effect identifying with them.

The auto-da-fe that is Burning Memory “evokes the annihilation of ideas,” as Wood says-it evokes the book burning of the Nazis, that is, the anti-intellectualism that accompanies anti-Semitism, and more broadly the burning alive of heretics by the orthodox establishment-but it also, paradoxically, shows that the heretical ideas, and the past, remain alive however ostensibly annihilated. Burning Memory is a funeral pyre, but it is also the flames in which the phoenix renews its being. However strange it may seem to say so, The Last Journey is a new beginning: a beginning in memory. There what is last becomes everlasting-what is repressed becomes irrepressible. The victims of history become sacred in memory-what we would prefer to forget becomes unforgettable: eternal. Wood’s work is double-edged, for what has been lost is found again in memory-indeed, remains fixed and felt in memory, an idee fix of feeling given memorable form–even as memory shows that it is dead. Wood’s work burns itself into our memory, even as it tells us that memory is the corpse of history. The flame that annihilates and the flame that is eternal are indissolubly one in her work.

As the holocaust recedes into history, its significance tends to be forgotten, but Wood overwhelms us with it by burying us alive, as it were, in the memory of it. She reminds us that it was the climactic pogrom of ideas as well as people: she rescues-¬relentlessly excavates, one might say, like an obsessive archaeologist-some 700 books and newspapers dealing with it, directly or indirectly. They are the dead bones of the holocaust, but her work shows that they are uncannily alive. She gives them body, as it were, by accumulating them: each is a fragment of feeling and tissue of thought, arranged in an assemblage that conveys their abundance while acknowledging their incompleteness: more can be found, in whatever dustbins of society. Wood’s work is overwhelming, intimidating evidence of man’s inhumanity to man, a painful abundance of physical memory traces which she makes more overwhelming and intimidating by piling them up, seemingly randomly, in a monumental, totemic reconstruction of history, which immediately deconstructs into a catastrophic ruin. Art historically her work is an accumulation, but humanly speaking it is a morgue. Like a gleaner in an abandoned field of time, she finds timeless food for thought in thoughtless human behavior.

Burning Memory is a masterpiece of death, and has the physical and emotional presence-not to say tortured materiality and mentality–of living death. Wood in fact has an extraordinary feel for material-a sort of haptic as well as visual sensibility. Indeed, her work is physically raw, forceful, confrontational, and threatening, making it even more visually striking, not to say violent and terrifying: violence and terror are its subtext. It bombards us with historical information in raw physical form, literally embodying and visually immersing us in the catastrophe of the holocaust. The holocaust is implicitly ongoing and unfinished, a symbol of perennial suffering and the death drive-which is why the holocaust has an unconscious grip on us–as well as a particular historical event, the “final solution” to the “Jewish problem” with no final solution to the problem of its meaning: more and more historical material can be found and added to Wood’s work, suggesting that it is a work in perpetual process, a work that can reach to the sky like a tower of Babel. Wood’s Burning Memory is an unfinished masterpiece, for there is always more material to find, more suffering to acknowledge, more futility, helplessness, and rage to feel: her auto-da-fe is an ever-expanding cosmos of bleakness, a triumph of the all-encompassing negativity that is death.

The many languages in her tower suggest the many meanings of the holocaust, and more broadly show that Wood can read the language of death with an ease that suggests it is her natural language: she is not only the historian of death but its oracle. Her tower seems on the verge of collapsing, perhaps because it seems haphazardly built, perhaps because it is unable to contain its sprawling contents, as though they were too horrible to bear-there is no hierarchical order structuring of the texts, no priority of one over the other. They are all rubble, and we are always in danger of being crushed by the rubble: we too can become sudden, unprepared victims of a holocaust. Wood may have what psychoanalysts call a rescue fantasy, but morbidity seems ingrained in her work, suggesting that she finds it hard to awaken from what James Joyce called “the nightmare of history,” or, as I would prefer to say, to escape the pathology that history makes evident. (Wood’s 1999 film, Memory of the Century, dealing with the Vietnam and Cambodian wars and the genocides in Rwanda and Kosovo, makes it clear that holocaustal destructiveness was a constant in the twentieth century, which Hobsbawn and other historians have argued was the most barbaric of all centuries, by any standard of measurement.)

The debris of the holocaust-vacant signifiers, to use the philosopher Mikel Dufrenne’s felicitous term, which Wood fills with fresh meaning by bringing them together in her work, where they sort of explosively interact-is mounted on a section of railroad tracks, a synecdoche alluding to the famous railroad tracks that led to the gates of Auschwitz. I suggest that these straight and narrow railroad tracks-stable and predictable compared to the unstable and bizarre structure they support–symbolize the “ruthless logic” that issued in the inhumane efficiency of the holocaust, to refer to the epigraph from Broch. It is the existentially indifferent logic of modem rationality-what Adorno calls the logic of instrumental reason at its most banally perfect and aggressive. It is a stroke of genius to mount the debris of the holocaust on these railroad tracks: with a sort of extravagant directness, Wood brings what is in effect the end of the journey to Auschwitz together with its beginning: the train is the machine with which it began, and a harbinger of the machines-gas chamber and crematorium-in which it ended. Wood has come full circle, as it were, making the inescapable logic of routinized death self¬-evident.

L’Espace d’un Instant, 2010 also makes brilliant use of the railroad tracks: the figure sized lead flowers, marked with numbers, are in effect the ghosts of the victims who perished at Auschwitz. Always concerned “to draw life from death,” as Wood said with respect to Memory of the Century, 1999-an installation of nineteen trepanned pink skulls, alluding to her father’s death, as she says, more broadly, to the victims of Auschwitz (the two civil engineering signs suggest what has been called the “industrialization of death” at Auschwitz)-also suggest the renewal of faith in life that was lost at Auschwitz. To refer again to Broch, the flowers have “the simple sufficiency of existence,” the “concrete life” that was destroyed at Auschwitz. But, again, and as always with Wood, the work is paradoxical, not only in meaning but by way of its material: the flowers are made of lead, a dead material-as dead and ironically soft as the old newspapers and books in Burning Memory. Thus once again we have death-in-¬life and life-in-death: the alchemists wanted to convert lead into gold, but Wood’s flowers suggest that the conversion is not complete. Lead becomes the gold of art in Wood’s hands, but the flowers are too gray to have grown in a pastoral golden age. They are the flowers of mourning left on a mass grave, withering like the bodies in it. Perhaps they also symbolize the weeds that grew between the tracks when the war was over and Auschwitz was abandoned. Indeed, there is an air of profound abandonment to Wood’s deceptively simple work. The flower is reified, a kind of pillar of salt in the moral desert symbolized by the railroad tracks, a petrified figure left behind by a volcanic explosion reminiscent of Pompeii-and among Wood’s many materials is volcanic stone-its life stopped in its tracks, its growth arrested, suggesting the absurdity of life even as it conveys life in its most lovely, memorable form.

Wood has called herself a “memory collector,” and the memories she collects are of suffering-perennial suffering, to reiterate. She has turned her memories into a kind of “concrete poetry,” confirming Adorno’s admission that it is possible to write poetry after Auschwitz-and about suffering and its inevitability, historically as well as personally-but what makes her poetry truly eloquent and poignant is that it shows that it is possible to go on living after Auschwitz however much it has destroyed one’s faith in life and humanity. Wood’s “dream of humanism was fractured”-thus the fractured character of her work, the sense of brokenness and despair that inform it-by her adolescent discovery of “the archives of the Nazi camps,” as she has said. She realized the widespread “love of hate” in the modem world-the holocaust showed that the hatred of the Jews was its primary symbol-and attempted to counteract it by representing it in her art: “my only salvation lay in my Art,” she has written-and salvation, paradoxically, turned out to mean representing hatred and its destructive effect. As strange as it may seem, by representing her loss of faith and the suffering it caused her, and more broadly, the destructive suffering at large in the world-by personalizing and poeticizing that impersonal and commonplace suffering in and through her art-she restored her faith in life and humanity, however hesitantly and uncertainly.

Freud thought of psychoanalysis as a kind of archaeological enterprise in which one recovered the past and with that the feelings associated with it-“hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences,” he famously said. “These memories correspond to traumas that have not been sufficiently abreacted,” resulting in “strangulated affect[s],”(7) Wood’s art is a kind of archaeological enterprise, suggesting that it is a form of self¬-analysis, keeping her sane in an insane world-a world whose insane destructiveness she documents to avoid becoming destructively insane herself. Incorporating archaeological fragments of society’s insanity in her art is in effect a mithridatic act that gives it an apotropaic function. She wards off society’s evil-its evil eye, as it were, that is, an eye that looks with hatred at what it sees, and intends to destroy it with that hatred–by incorporating the remnants of things that it has destroyed, and that remind us of its destructive power: her archaeological fragments are rotten with death-but, strangely, they have survived it, as though emotionally blessed rather than physically cursed. Every piece of material Wood recovers from the past, every aging detail of memory scarred by entropic suffering-“metal that has been corroded after a long immersion in the waters of a lake, lead from old rooftops, archaeological wood dating back to the Bronze Age,” as she has said-testifies to the psycho-archaeological character of her art. Especially because each and every one is the physical residue of an affect that is no longer strangulated but rather openly and emphatically, not to say vehemently expressed in her art. They are fragments of her self, and her own past history, recovered through and dramatized- majestically abreacted-by her art

It is in fact extraordinarily dramatic-tragic theater, with the archaeological fragments, whatever their traumatic physical character, playing starring roles. Her works are stages on which she enacts her suffering, an expressive enactment that transforms it into a capacity to empathize with those who have suffered more greatly than she has, however great her suffering: the victims of the Holocaust. They have suffered unto literal death, to play on the existential philosopher Soren Kierkegaard’s famous phrase, not only psychic death. They cannot tell the tale of their suffering and disillusionment with life and society, which is what Wood does for them by working through her adolescent suffering and disillusionment in her art: it turns out to be a maturing moment of enlightenment rather than of self-indulgent suffering.

What is truly unusual about Wood’s art is that it gives us a sense of the holocaust as it happened and must have been experienced by those who died in it, indicating that she sees it from the inside-as a desperate participant not simply a detached reporter, and thus with greater insight than any of the reports of it she uses in her art. Wood’s passionate response to the holocaust subsumes her objective knowledge of it, suggesting that for her unless one identifies with its victims, and suffers body and soul what they suffered body and soul, one cannot fully “realize” let alone understand it. This is why she is prepared to bum the huge amount of archival information-all a sort of intellectualization of the holocaust–she has accumulated over the years in the auto-da-fe that is Burning Memory. For Wood, imitatio Judaeus has replaced imitation Christi.

Notes

-

(1)Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes (New York: Vintage Press, 1996),43

(2)Hermann Broch, The Sleepwalkers (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1964), 447

(3)Theodor W. Adorno, Negative Dialectics (New York: Seabury Press, 1963), 362-63

(4)Sebastian Vilar Rodriguez, “All European Life Died in Auschwitz”, Barcelona newspaper, January 15, 2008

(5)Quoted in Michele C. Cone, “Vampires, Viruses, and Lucien Rebatel: Anti-Semitic Art Criticism During Vichy,” The Jew in the Text, eds. Linda Nochlin and Tamar Garb (London: Thames & Hudson, 1995), 178

(6)Eric Hobsbawm, “Barbarism: A User’s Guide,” On History (New York: New Press, 1997), 253-54

(7)Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud, Studies on Hysteria (New York: Basic Books, 1957), 7, 10, 17

Memoire en Flamme (2010)

(detail) 220 x 329 x 185 cm,

Installation 700 livres environ,

journaux datant de la 2eme Guerre Mondiale,

rails de chemin de fer,

balastes, traverses.

The Last Soup (2000-2010)

60 x 150 x 135.5 cm

Cing mains en platre,

une ecuelle et cinq cuilleres,

trois sacs de toile,

rails de chemin de fer,

balastes, traverses.

The Last Soup (2000-2010),

(Detail) 60 x 150 x 135.5 cm

Cinq mains en platre,

une ecuelle et cinq cuilleres,

trois sacs de toile,

rails de chemin de fer,

balastes. traverses.